Hello

It’s been a while since my last post. I hope the infrequency has at least given a gentle pause, and I hope all is as well as it can be. This website had a little meltdown earlier on in the year, so my blogs for the last few months are also missing. You can read them here on substack. Here we are in this time of long sunlight hours.

Open Practice also paused last month and will begin again Monday 13 May 2024 at 6.30pm, on Zoom. Then the next two open practices will be Monday 15 July and Monday 12 August, 6.30pm.

Before I go on, a big shout out to Elsa and Claire for identifying the amphibian from my last missive as a common frog (not toad). Thank you!

When I wrote the initial version of this post in early April, the air was damp and chilly, bird nesting season had begun, and I was considering being comfortably uncomfortable. Jackdaws sped past my window with faster and faster frequency carrying moss and twigs. I watched a glorious Jackdaw, on the unforgiving tarmac, working a long twig at least three times as tall as them. The twig had an uncomfortable sticky out bit on it. Twisting this extra awkward stick round and round, the effort briefly stopped whilst the Jackdaw stood back and viewed the stick sideways from each bright pale eye. Then went back in, manoeuvring feathers and beak and body into a position where flight was just about possible. The effort for the upward energy and motion to leave the ground seemed so massive. I wonder if the Jackdaw knew it was manageable. Maybe it was a practiced manoeuvre, or perhaps not knowing is part of pulling off seeming impossible feats. That stick looked seriously challenging to balance and carry. Despite this glorious invitation to confidence, I lacked the courage to post my writing, which sometimes happens. Better late than never…I was fearful of not managing to be of service to anyone reading. I also wanted to post an audio meditation, but couldn’t quite get it ‘right’. If you might like an audio, do drop a note in chat. If it feels of service I may well do it!

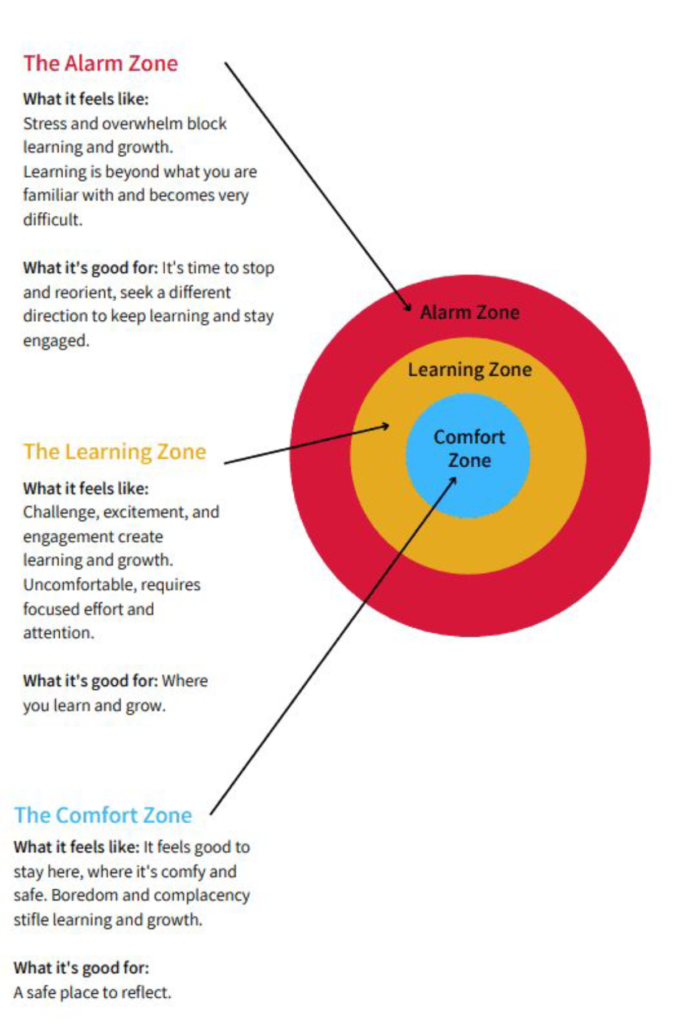

I’ve written much previously on being comfortably uncomfortable. My now very old PhD publication is infused with an exploration of the subject in the lives of experienced creative practitioners and artists. Last week, I facilitated two days with 64 million artists. The consideration of discomfort surfaced in these workshops. 64 million artists use a learning zone model that I’ve used before (see below).

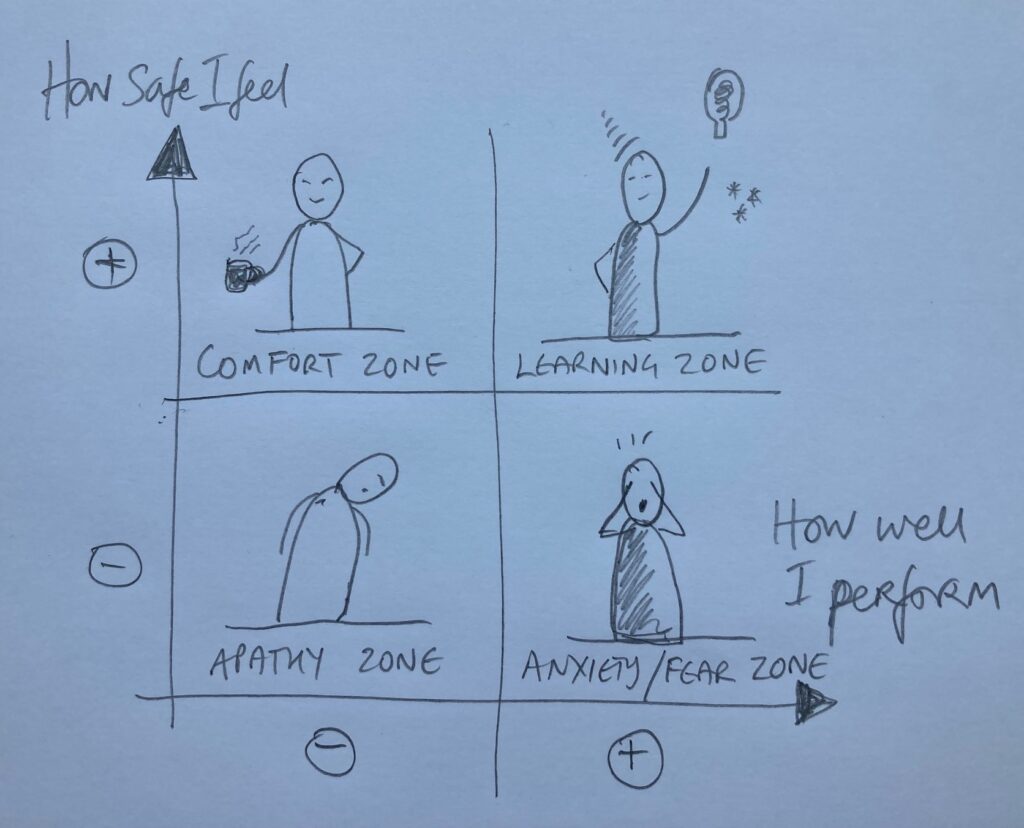

Behaviourist Amy Edmundson published a much discussed article on ‘psychological safety’ in learning environments in 1999. Both the learning zone model above, and a reworked model that I also use, see below (based on Edmundson), suggest we require a high degree of psychological safety to be open, experiment, and stay in discomfort without fear. In any setting, it is important to be able to operate from a place of safety, in groups and individually.

The theory goes that the ideal place for learning is in that middle orange circle, or in the +/+ side of the matrix. When we are moving out of our comfort zone into a more stretching and learning zone, but remaining in our space of learning, not heading into fear. We are also bolder when we’re in the +/+ zone of learning. Able to find the courage to own our mistakes, to support others to own their mistakes; and feel able to suggest our maddest ideas, or think more freely. Psychological safety is not to be confused with forced optimism, toxic positivity, faux smiles, or pleasing and praising. It means feeling safe enough wherever you are, to be able to be yourself, address mistakes and be able to express your ideas without concern for a backlash.

Yet, Georgia O’Keeffe, fabulous artist said:

‘I’ve been absolutely terrified every moment of my life and I’ve never let it keep me from doing a single thing I wanted to do’.

Maybe O’Keeffe isn’t the best role model for looking after ourselves in a safe way! However, I’m curious in how we know (and how we may be able to recognise in time), when we’re in stretch and when we’ve headed into fear or downright terror. What does stretch feel like to you and when do you know you’ve overdone it? For O’Keeffe it seems that she did not recognise a ‘just the right amount of uncomfortableness’ learning zone, yet she went ahead and did anyway. The amazing mindfulness teacher Joseph Goldstein uses O’Keeffe’s quotation, in his teachings on accepting fear. Goldstein uses the phrase ‘it’s okay to feel this’. Of course, this is one sentence from O’Keeffe. The diagrams above are good to think with, yet are only theories. Joseph Goldstein’s magic phrase of ‘it’s okay to feel this’ works for me when I need to accept discomfort, and considering whether I have overdone or underdone my ‘stretch’.

Paying attention to how we feel, and allowing ourselves to feel what we are feeling in our body, for it to be okay to feel. To notice when we are chasing comfort when being human is so uncomfortable so much of the time. Embracing that. This seems to me to be part of allowing ourselves to be whole. I wonder what you think? When do you notice a sensation in your body and when are you labelling something in your head, but maybe not connecting it to your body?

We don’t know what’s going to happen in the next moment, so how can we know when a particularly awkward and challenging (metaphorical or actual) stick is worth the effort of solving the puzzle and picking it up, and when is it best left alone? Can we ever know without the benefit of hindsight? Stick or not, being challenged comes with daily living one way or another.

To return to Jackdaws. I’ve had the privilege of having a rowdy group of Jackdaws living adjacent to my sleeping space for the last few years. Their vocabulary is immense and intense. Sometimes they sound like they have nicked a bag of dog squeaky toys and are trying to break them with high velocity chewing. Other times their ‘jack-jack’ is emitted with perfect enunciation and voice throwing. They are usually in pairs, and like other Corvids, Jackdaw pairs generally stay together for life. Jackdaws can recognise individual humans, and I’d invite you to make a connection with these super intelligent awesome beings. So often they are seen as vermin, and yet their needs, comfort and existence are tied up with ours. They are also fascinating!

Until next time, wishing you the best size carry-able sticks at the most appropriate time. Karen